I’m writing this on the second day of the impeachment trial in the Senate. I haven’t even checked on today’s impeachment news yet, and I have no idea how the trial will end. (Actually, it’s pretty clear what the verdict of the GOP-controlled jury will be, but what we don’t know is how it will play out and how it will affect public opinion.) Nevertheless, I feel like the most significant plot twist of the entire affair has already occurred — late last night when most of America was no longer tuned in.

I’m writing this on the second day of the impeachment trial in the Senate. I haven’t even checked on today’s impeachment news yet, and I have no idea how the trial will end. (Actually, it’s pretty clear what the verdict of the GOP-controlled jury will be, but what we don’t know is how it will play out and how it will affect public opinion.) Nevertheless, I feel like the most significant plot twist of the entire affair has already occurred — late last night when most of America was no longer tuned in.

At the very end of a series of amendments offered by the Democratic House Managers seeking subpoenas of various individuals and documents (all of which were voted down along party lines) a final amendment was offered that was unlike any of the others. This 11th amendment of the long day would have given the judge presiding over this trial the power to rule on the relevance of any witnesses or documents that either side might wish to subpoena.

On the surface, this might seem to be such a natural way of handling subpoenas that it shouldn’t even have required an amendment to the original rules. After all, isn’t it always a neutral legal expert like a judge who determines whether witnesses or evidence in a trial is admissible and relevant, or whether subpoenas are valid? Wouldn’t it be crazy if it were, say, one of the attorneys, either for the defense or the prosecution, that had total control over what testimony and other evidence got to be presented in a trial?

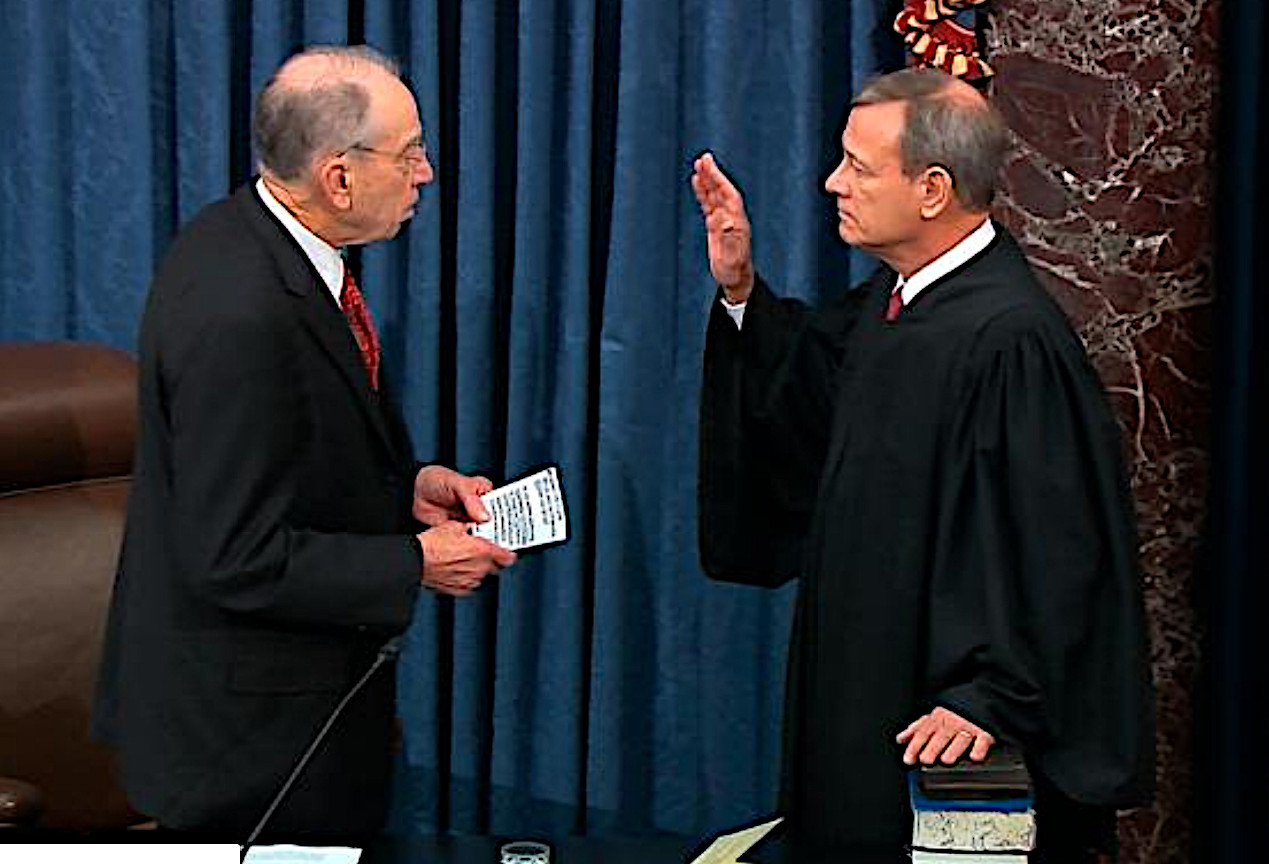

But even more surprising than the fact that such an amendment was needed, was who offered it: the Democratic House Managers. Why was that surprising? Because the judge in this case is John Roberts, the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court — and a conservative Republican who was appointed by George W. Bush and almost always votes on the side of the 5-4 conservative majority on the court.

The debate over witnesses has not been a simple one because it’s not just a question of who has the power to say yes or no. That question has a simple answer: the Republicans, who control the Senate, can strictly do whatever they want. The complications arise because they have to be careful about how their actions will affect public opinion. If they could have followed their immediate impulses, there wouldn’t even be a trial right now. They could have dismissed the whole thing from the start. But then what would the public think? How would that affect the reelection chances of some of their more vulnerable members, not to mention their President?

Likewise, the Democratic House Managers know they’re going to be outvoted at the end, but their hope is to present as compelling a case as they can to the American public.

For both sides, the appearance of fairness is critical.

Given that reality, why were the Democratic House Managers willing to put their fate into the hands of a Republican judge? If they just let the GOP outvote them over every single witness and document, then they can at least claim that they’ve been railroaded. The public would witness one 53-47 party line vote after another, and some moderates or independents might be swayed toward the Democratic side by the clear significance of that pattern of votes. But if it’s the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court striking down your desired witnesses, it’s much harder to claim it’s a partisan power play. No GOP senator would need to go back to their home state at election time and explain why they voted No on any given witness or document.

So why did the Democratic House Managers invite that scenario? Because they didn’t believe Roberts would rule against their witnesses and allow the GOP witnesses, even though he’s a Republican. They honestly believed in the facts and legal principles behind their case, and even though they disagreed with Roberts’ politics, they still believed him to be an honorable man and an expert in the law who would make his rulings in an unbiased way.

(And I think we should just pause a moment to appreciate the value of that gesture in this period of such extreme partisan rancor. The Democratic House Managers might not think much of the President’s attorneys or the GOP senators, but they respect John Roberts.)

The GOP, however, despite the P.R. cover it would have given them, voted this amendment down unanimously, adding to the day’s glut of party line votes. Why did they do this?

Because they knew that, despite the fact that Roberts is a Bush-appointed conservative Republican justice who has voted on their side in the vast majority of cases that have come up in the Supreme Court, he was not going to vote on their side in this trial, because their case was based entirely on power and not on truth. (As expressed earlier in the evening by Trump attorney Pat Cipollone’s angry snarl at Democratic House Manager Jerry Nadler, “You’re not in charge here!”) They knew that, as much as Roberts might want their side to win, for partisan purposes, he would not compromise his legal judgement to help that happen.

John Roberts was the only honorable Republican left in that courtroom, which made him unfit for current Republican politics.